The Human Body as a Microcosm: Art, Anatomy and Astrology

Exhibition Overview

Since ancient times, the human body has been gazed upon in various perspectives. Through art seeking an ideal, anatomy revealing its nature, and astrology exploring its celestial connections, our aesthesia, intellect, and imaginations have indeed produced vast images of the body.

This exhibition is comprised of about 140 pieces ranging from ancient prints to those of contemporary Japanese artists, introducing a collection - or a microcosmos - of the bodily world. Can be seen, are the numerous body figures competing their beauty, throbbing with force, and irradiating with the stars.

April 20 - June 23, 2019

Chapter 1-1 Ideal Bodies: Beauty / Proportion

We first pick up on how the human body has been depicted in the western civilization. In this section, ‘Beauty’ revolves around the balance and ideal of the body’s proportion. Scoping in the late 15th to 16th century, it was an era flourishing with the revival of ancient Greek and Roman culture, the coming of the so called ‘the Renaissance.’

Ancient sculptures and carvings were excavated in this era, which were set as models for the artists of the time. In the center stood Italy, where many ruins remained. One of the artists who absorbed the ancient norm into his flesh and blood, was Michelangelo.

Intriguing theories were found as well. Vitruvius, an architect of ancient Rome wrote that the circumference of an outstretched human body fits perfectly in a square. These words were illustrated and diagrammed by Leonardo da Vinci, and numerous others to come.

Also greatly studying from these sculptures and theories was Albrecht Dürer, who further built his own theory of depicting the human body through practice. From the copperplate prints Nemesis to Adam and Eve, and from the series of The Engraved Passion to the theoretical Four Books on Human Proportion (Hierin sind begriffen vier bücher von menschlicher Proportion), Dürer continuously explored the ideal figure of the human body.

Chapter 1-2 Ideal Bodies: Energy / Power

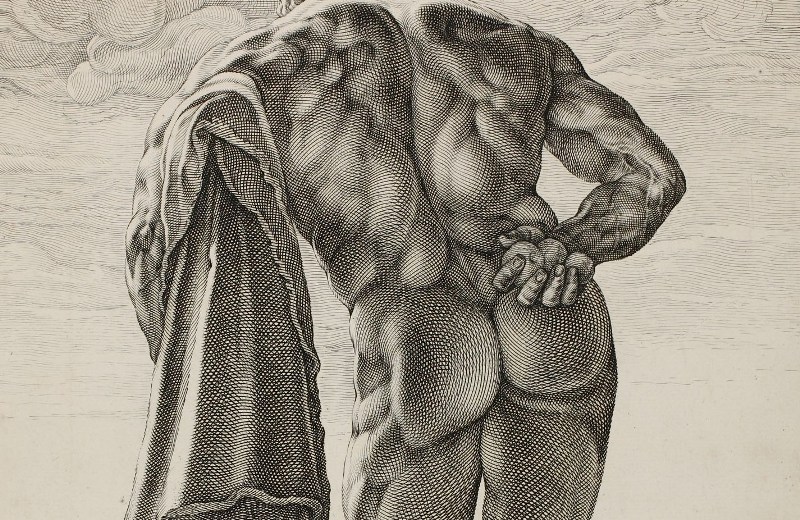

Next, we exhibit the expressions of ‘energy’, in masculinity and bodies in motion, along with the ‘power’ of armies and regimes. It is the 16th to 17th century, an era when the dictatorial structure centering on the feudal system changes, as the Middle Ages ends.

Sure to be an icon of these masculine figures, the legend of Hercules and his great heroic acts were stories that men in power fancied, and as for artists, was the ideal model to draw a strong body and its grand movements it was capable of. On the other hand, mercenaries and militias would start to appear in drawings of the 16th century. This concurs with the focus of war, shifting from the power of individuals like knights to the power of loads, of organized troops.

The 16th century was also a period when swordery and combat techniques passed along in manuscripts, were then widely spread through printing technology. We can see how the analyzation and explanation of ideal bodily motions reproduced in prints, enabled anyone to practice the same moves.

The shift of power from ‘a hero’ to ‘troops,’ is reflected on the imagery of regimes as well. Seen from its inscription on the bottom, The Farnese Hercules carved by Hendrik Goltzius can also be taken as an expression of Netherlands’ enhanced national prestige. On the contrary, the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan depicts countless people gathering to form a huge politic body, or so to say, a nation.

Subchapter Sacred Bodies

Another ideal that we could not leave out when speaking of western bodily images is that of Jesus Christ, the body which was tortured and crucified upon atonement for the sin of Adam and Eve.

A scene of Christ’s Passion, the Arma Christi (instruments of Passion) placed around a blood shedding Christ, the instruments arranged inside a heart, and an infant Christ holding a whip… the depictions stretch to numerous variations. All are unembellished woodprints that are carefully hand painted, bringing the owners’ faith in mind.

The aesthetic of Christ’s body was also passed on to his followers. In The Golden Legend (Legenda Aurea Sanctorum), a collection of the saints’ lives, the scenes of the Saints persecuted for their faith are seen in various illustrations. However, these Saints were not solely object to devout feelings. For example, the depiction of St. Stephan who had his head crushed by stones was solicited upon to cure headaches, while St. Sebastian’s arrow wounds evoked pest scars, which were then believed to cure the pest.

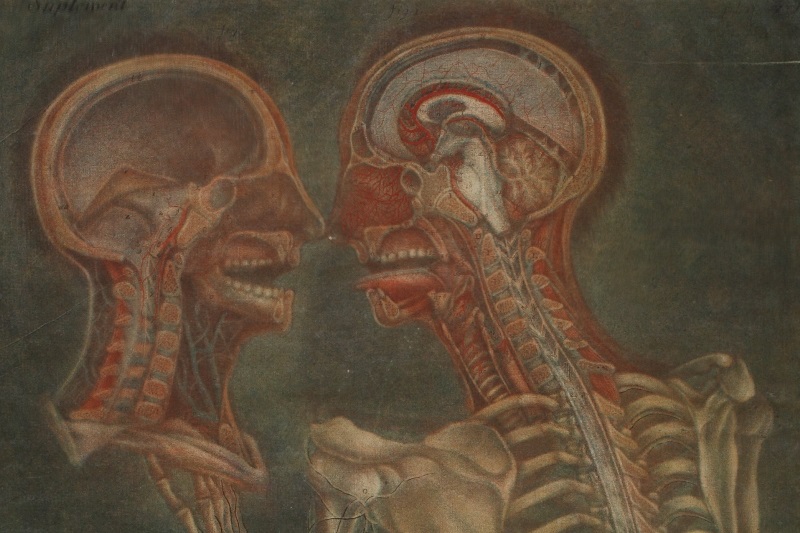

Chapter 2 Anatomies in Dreams

Following the perspective of art and religion, this chapter exhibits the western body through the eye of science. What we look at is the human body pictorially dissected from the end of the 15th, to the mid-18th century. Some may well be inaccurate compared to today’s anatomy, but hence many have their own unique charms.

Take Bartholomaeus Anglicus’s Creation of Eve from On the Properties of Things (De proprietatibus rerum). A dissected figure is standing outside Paradise. Even 200 years later, in The Sacred Physics (Physique sacrée) by Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, one can see the strange combination in which religion and science is inseparable.

Anatomy was also the merging point of science and art. The famous Andreas Vesalius’s On the Fabric of the Human Body (De humani corporis fabrica) is sure to be a terminus. With the anatomy performed by the author himself, the skillful strokes of the sketches, and the expert hands of carvers, anatomical chart s of outstanding balance and dignified physique were produced, with its beauty that could be on par with ancient sculptures.

These were Écorché, created upon the mixed perspectives of science, religion, and art of the time. Each were explored in earnest, which may be the reason why these anatomical drawings may even look mystic to our eyes from a different era.

Subchapter The Architectural Anatomy of Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Prominent as a ‘paper architect,’ Giovanni Battista Piranesi viewed ancient Roman ruins as an archeologist, and delineated them on plates. This subchapter observes how the methodology of his illustrations are similar to anatomical diagrams. Shown are architectural drawings from Roman Antiquities (Le Antichità Romane).

Just as the ‘Vitruvian Man’ bespeaks, the analogy of the human body and architecture was not an uncommon view, as we can well recall a dissected figure standing in front of a ruin in Vesalius’s On the Fabric of the Human Body. It wouldn’t be any surprise if Piranesi had viewed the appearances of collapsed ruins with its bare structures, as similar to anatomy revealing the organs under its torn skin and tissues.

Roman Antiquities directs its interests from the landscape illustrations of the ruins, to the noticeable details. Thus, its cross sections unfold in turns, as if flesh and tissues get peeled off the skeleton.

In the mid-18th century when these were made, Gautier d’Agoty had diagrammed an anatomy of the human body from whole to detail, in a similar manner to Piranesi, as we saw in the last chapter. As of the layout in which the central subject is diagrammed on a piece of paper depicted inside the drawing, it could be very well said that this is the same rhetorical method to Scheuchzer’s The Sacred Physics which too was published in the same period.

Chapter 3-1 The Human Bodies as Microcosmos

As seen by now, we have realized our interests in our appearance and inner body through various notions and perspectives. Furthermore, we also have attempt to position ourselves in distant space. In this 3rd chapter, we drift among the various images devoted to the connection of astronomy and anatomy, and the microcosmos that dwell inside our bodies.

First to encounter is a queer image called the ‘Zodiac man.’ It shows the 12 signs of the zodiac, controlling 12 parts of the human body. Thus it was believed, that any medical treatment of a specific body part had to be operated when the corresponding constellation rose.

The view of coordinating the human body to the stars was not limited to astrology. The sun and moon drawn with a face is surely an oldest and fundamental example. This personification never ceased to exist, even after astronomy became a scientific study. The works of J. J. Grandville, that sought a reflection of Paris’s society on the constellations, is a descendant of this primordial imagination.

We also cannot leave out the divine beings of ancient Greek and Rome, who still mark their names on the planets and stars today. These deities whom had lost their true appearances during the middle ages, restored their ideal forms in the renaissance. The gods and goddesses were again, an existence that influence our bodies as the constellations.

Chapter 3-2 Hitoshi Karasawa, Toshihiko Ikeda, and Mihoko Ogaki

Finally, we gaze at the connection of the macrocosmos and the body, to the microcosmos spreading inside. Introduced are Hitoshi Karasawa, Toshihiko Ikeda, and Mihoko Ogaki. Each have given form to their inner worlds through their original eyes, hands, and imaginations. However, they hold a similarity in the aspect they imply: Life and death, a root element of the body.

Karasawa pours life into images excavated from the numerous layers from the history of prints and writings, while Ikeda portrays the ‘power’ residing in and after old age, as monstrous appearances. The former shows correspondence to other works all throughout this exhibition, and the latter overlaps with the humour and paradoxical vibrance of the Écorché on the prints.

As of Ogaki’s work gleaming in the darkness, it does not just remind us of the connection between our bodies and the stars. The moment we notice that the light projected is lit by ourselves, we would feel the utmost reality that the ‘body’ may very well be the ‘cosmos’ itself.

Exhibition Summary(PDF)

List of Exhibits(PDF)

Author

Takuya Fujimura (Curator, Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts)

Translation

Tomoya Kato