1200 Years of Japanese Prints: Receiving, Interacting, and Emerging

Greetings

We are pleased to present the exhibition “1200 Years of Japanese Prints: Receiving, Interacting, and Emerging.”

In Japan and other parts of East Asia, printmaking has long served as a medium for both supporting people’s religious faith and enriching their daily lives. Since the modern era, under Western influence, printmaking has established itself as an art genre, and today Japan is considered one of the world’s most active countries in printmaking.

Since its opening in 1987, our museum has been collecting, preserving, and researching prints from around the world and throughout history. As a museum specializing in prints, our collection now comprises approximately 33,000 works. Furthermore, through our past independently curated exhibitions, which have explored the history of cultural exchange through prints, we have demonstrated how a single print can transcend national boundaries, connecting people across cultures and giving birth to new forms of artistic expression.

Building on the museum’s activities to date, this exhibition will reinterpret the 1200-year history of Japanese prints with a focus on stories of cultural exchange. For instance, when we look back at history, just as Japan’s world-renowned ukiyo-e prints flourished by incorporating artistic techniques from China and the West, we can see that behind what is considered as uniquely “Japanese,” there lies interaction with artworks and people from diverse cultural backgrounds.

The exhibition showcases about 240 carefully selected works from our collection, with particular attention to connections with other East Asian countries. The exhibits range from Japan’s oldest extant printed material, the Muku Joko Daidarani-kyo, to Buddhist prints, painting manuals, ukiyo-e, sosaku-hanga (creative prints), shin-hanga (new prints), postwar prints, and contemporary prints. We invite visitors to ponder how printmaking, which we consider both “tradition” and “art, has evolved and where it is heading. Let us embark together on this 1,200-year journey of “Japanese prints.”

Finally, we would like to express our deepest gratitude to all those who have contributed to the realization of this exhibition.

March 2025

Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts

Director, Jun’ichi Okubo

Exhibition Information

| Exhibition Name | 1200 Years of Japanese Prints: Receiving, Interacting, and Emerging |

|---|---|

| Duration | Mar. 20(Thu.) 2025 - Jun. 15(Sun.) |

| Admission fees | Adults ¥800 (¥600), University and high school students ¥400 (¥300), Junior high school students and younger free of charge. |

Exhibition Outline

Our museum houses prints from various ages and cultures, and has one of the largest collections of Japanese prints in Japan. This exhibition presents prints from the Nara period(8th century) to the present day from the perspective of cultural exchange, shows visitors to enjoy the museum's masterpieces.

Exhibition Layout

Chapter 1: Prints and Prayers – The Dawn of Japanese Prints

The history of Japanese woodblock prints began with the introduction of Buddhist art from the Korean Peninsula.

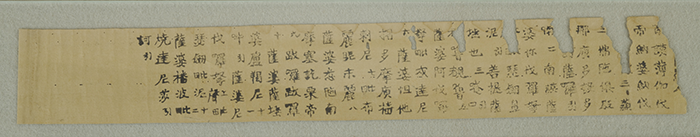

In 764, during the Nara period (8th century), Empress Shotoku, concerned about the state of the country, which had been ravaged by civil war, had placed Hyakumanto (No. 1-1) in various temples, praying for the protection of the nation and the repose of the war dead. Inside these pagodas was the Muku Joko Daidarani-kyo (No. 1-2). It is considered Japan’s oldest surviving printed material. While its printing technique can be traced back to India, many details about its production method remain unclear.

Muku Joko Daidarani-kyo (printed Buddhist scripture contained in the Hyakumanto),764〜770[exhibited until May 6th]

During the Heian period (8th-12th century), Japanese woodblock printing flourished under the influence of the Chinese cultures of Tang, Five Dynasties, and Northern Song. Buddhist prints are categorized into two types in terms of techniques: “Inbutsu” (stamped Buddha images), created by pressing the block onto the paper from above, and “Suribotoke” (rubbed Buddha images), created by placing paper on the block and rubbing. “Seated Amida Buddha Suribotoke (100 images on one block)” (No. 1-3) and “Seated Amida Buddha Inbutsu (12 images on one block)” (No. 1-4) are early examples of Buddhist prints that were placed inside Buddhist statues, with multiple Amida Buddha images crammed together on the paper. In Buddhist prints up to the Kamakura period (12th-14th century), the various deities depicted were generally small in size.

During the Nanbokucho period (14th century), Buddhist prints began to change in character and increase in size. Some Buddhist prints created during the Muromachi period (14th-16th century), such as the “Twelve Devas (Yoda-ji Temple version),” were printed using woodblocks and then later hand-colored to be enshrined in temple halls as objects of worship.

In ancient and medieval Japan, printmaking evolved in close connection with religious faith.

Bonten(Brahman) of Twelve Devas, printed from the set of woodblocks at the Yoda-ji,1407[exhibited aftter May 8th]

Chapter 2: The Flourishing of Publishing Culture – The Dissemination of Images and Their Reception

From the 16th century, Jesuit missionaries began to travel to China to spread Christianity. The Western cultural items they introduced were received with great interest in China, and in 1696, Emperor Kangxi commissioned Jiao Bingzhen to create the “Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Agriculture and Sericulture” (No. 2-2). This work was done by incorporating the perspective drawing method learned from the Jesuits, and marked a departure from the previous spatial representation. Furthermore, the influence of Western painting also spread to the economic city of Suzhou. “The Wannian Bridge of Suzhou” (No. 2-6) depicts a new local landmark, showing the expression of unique perspectives that incorporated Western painting techniques.

During the same period, mainland China saw a flourishing of painting manual publications, with the production of works such as “Banzhong Huapu (Eight Varieties of Paintings)” (No. 2-11) and “Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden)” (No. 2-12), which served both as pieces to be appreciated and models to be copied.

Those painting manuals were imported to Japan, where they were reprinted and spread among the general public. Eventually, momentum grew for creating uniquely Japanese painting manuals. Artists in the Kamigata (Kyoto-Osaka) region such as Tachibana Morikuni (No. 2-13) and Ooka Shunboku (No. 2-14) published numerous picture books and painting manuals to guide emerging artists. In Edo, artists like Takebe Ryotai (Nos. 2-17,18) and So Shiseki (No. 2-19) published manuals to promote the Nanpin school style, newly introduced from China, but their paintings already showed signs of Japanese adaptation of Chinese styles.

Two beauties by a round window,18c[exhibited after May 8th]

ed.WANG Gai,Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden),1753

Chapter 3: The Ever-changing World of Ukiyo-e – Absorbing and Reinventing Foreign Influences

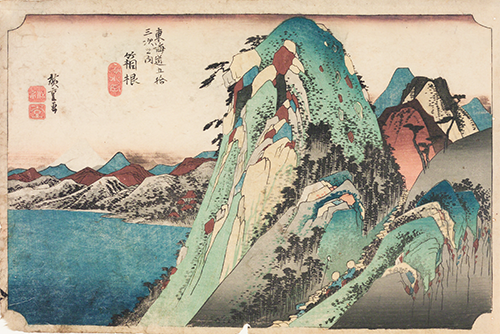

Japanese printmaking evolved in countless ways within the ukiyo-e genre under the influence of imported culture. This is evident both in terms of printmaking techniques and visual representation. One such example is uki-e (perspective prints) (Nos. 3-1,2), which emerged in the middle of the 18th century. Uki-e achieved an enhanced sense of depth in the picture plane using the perspective drawing method. This is said to have originated in Suzhou prints and Western paintings. In the 19th century, Katsushika Hokusai (Nos. 3-10~12) and Utagawa Hiroshige (Nos. 3-13~26) further developed the uki-e techniques and established a new genre of ukiyo-e landscapes. In addition, their contemporary, the popular painter Utagawa Kuniyoshi, employed Western-influenced shading techniques in his series, “Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety” (Nos. 3-27~30). This means that Western culture was always something that aroused the curiosity of people in Edo.

Ukiyo-e, which reflected cultural exchanges between the East and the West through the limited channels during the Edo period, began to vividly depict the various aspects of the modernization of Japan after the Meiji Restoration. As new printmaking techniques like lithography flourished, in his kosen-ga (light-ray pictures) (Nos. 3-48~51), Kobayashi Kiyochika, inspired by Western painting, captured subtle changes in light, such as the setting sun and candlelight, evoking nostalgia in people living in the changing new city of Tokyo.

In the modern era, when various printing techniques emerged, the role of ukiyo-e, which had absorbed foreign cultures with insatiable curiosity, eventually came to an end. However, new life sprouted from the legacy of ukiyo-e prints and would go on to spread its wings into the next world.

KATSUSHIKA Hokusai, In the Mountains of Totomi Provinces, from the Series "Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji",c.1831[exhibited after May 8th]

UTAGAWA Hiroshige, Hakone: View of the Lake, from the Series Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido,c.1833〜34[exhibited until May 6th]

Chapter 4: Sosaku-hanga and Shin-hanga – Eastern and Western Perspectives, Transcending Ukiyo-e

In the 1900s (Meiji 33-42), “sosaku-hanga” (creative prints) emerged, aiming to produce and promote original prints with high artistic creativity that maximized the effects of printing blocks.

The ideal of sosaku-hanga was for artists to be responsible for the entire process of “drawing, carving, and printing by themselves.” The artists, on the other hand, learned from traditional subjects, styles, and formats to create prints by paying homage to ukiyo-e, which was produced through collaboration between publishers, painters, carvers, and printers. Moreover, they were influenced by post-19th century Western art introduced to Japan, and incorporated its various aspects into their works.

Sosaku-hanga, created with eyes on both Eastern and Western perspectives, gave birth to uniquely Japanese expressions. In this chapter, among the artists of sosaku-hanga, those artists who paid particular attention to the tradition of ukiyo-e, such as Tobari Kogan (Nos.4-7~9) and Oda Kazuma (Nos. 4-10~15), will be addressed.

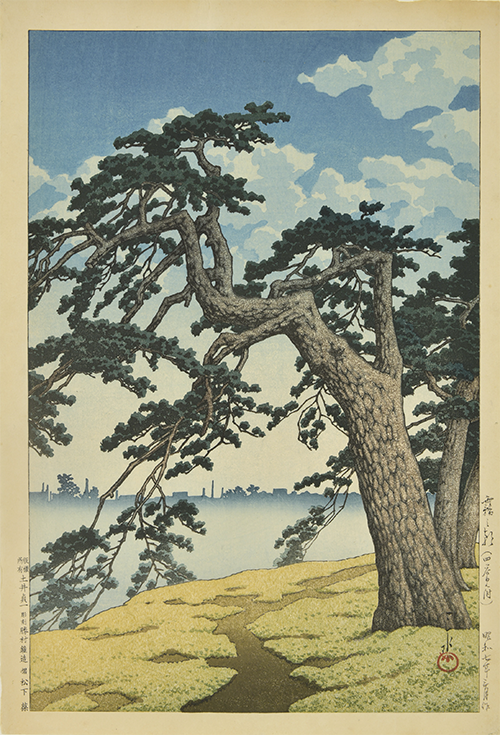

Meanwhile, in the early Taisho period (early 1910), Watanabe Shozaburo, an ukiyo-e dealer and publisher, established “shin-hanga” (new prints).

He sought to create prints using the ukiyo-e production system while resonating with sosaku-hanga for its pursuit of producing highly creative, original prints. He then expanded this movement internationally, particularly in the U.S., creating a movement for producing shin-hanga.

The artists of shin-hanga, while building on ukiyo-e prints, created works influenced also by Western art just as those of sosaku-hanga did, and established a new history of traditional woodblock prints different from ukiyo-e. Shin-hanga, also created with eyes both on Eastern and Western perspectives, became a modern Japanese print style that transcended that of ukiyo-e prints.

KOBAYAKAWA Kiyoshi,Figures in Modern Fashions Eyes,1930

KAWASE Hasui,Misty Morning, Yotsuya Approach,1932

Chapter 5: Networks through Print Magazines – The “Sosaku-hanga” Movements in Japan and China

The sosaku-hanga (creative print) movement sought to establish printmaking as a genre of fine art. Gradually, new forms of expression unconstrained by tradition began to be attempted. From the end of the Meiji period to the beginning of the Taisho period(1910s), new trends in European modernist art were introduced to Japan through art magazines and other media, and the prints of Fin-de-siècle Art and German Expressionism in particular captured the hearts of young artists. They tried to express their inner feelings by taking up sculpting knives themselves, and magazines like “Tsukuhae” and “Kamen” (Nos. 5-2,3) were born. Onchi Koshiro, a pioneer of abstract art in Japan, also began printmaking through this movement. The sosaku-hanga movement spread throughout Japan, and in the 1920s, sosaku-hanga groups were formed by professional and amateur artists across the country. These groups exchanged print magazines to form networks.

Fin-de-siècle Art and German Expressionism had an impact in China as well as in Japan. While studying in Japan, Lu Xun learned about the sosaku-hanga movement and from the end of the 1920s he introduced European and Japanese prints and proletarian art. Referring to the definition of sosaku-hanga in Japan, he went on to advocate its Chinese equivalent, the Chinese New Woodcut Movement.

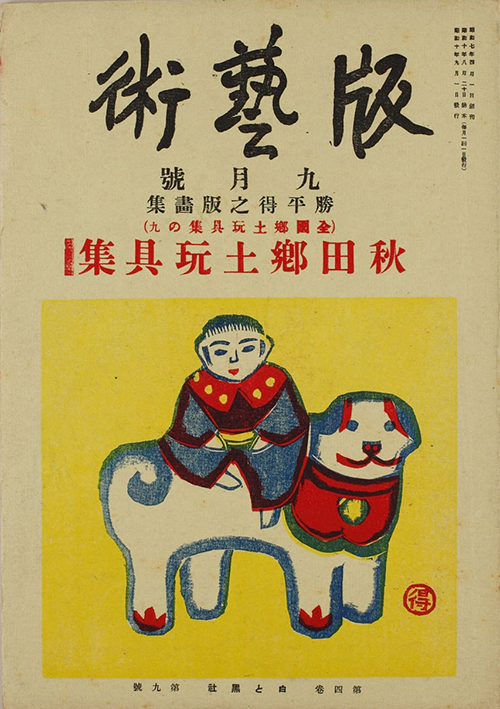

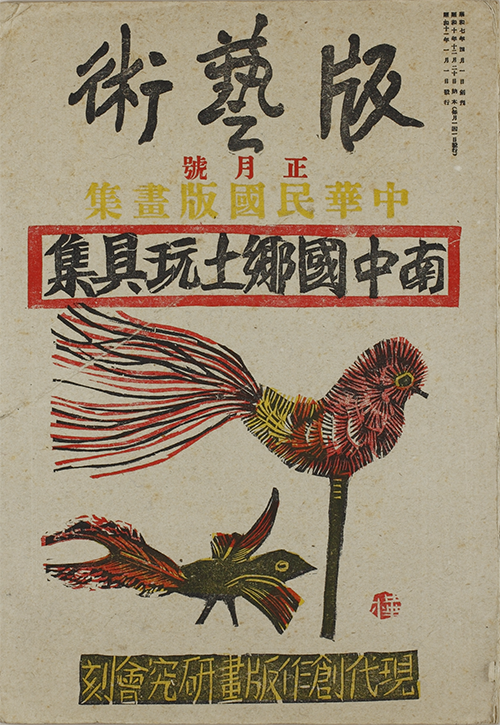

After New Woodcut groups were formed in China, exchanges with Japan’s sosaku-hanga groups began. In the early 1930s, Ryoji Kumata, an editor and printmaker, featured the “Xiandai Banhua Yanjiu-hui(Modern Woodcut Society)”, led by Li Hua, who were active in Guangzhou in the former’s sosaku-hanga magazines, reissued “Shiro to Kuro (White and Black)” (Nos.5-13-15) and “Han Geijutsu (Print Art)” (Nos.5-24,35). Additionally, the Chinese print magazine "Xiandai Banhua (Mordern Prints)" (Nos.5-35~42) has contributed works by Japanese printmakers.

However, after 1937, when Japan and China entered a full-scale war, young Chinese printmakers involved in the New Woodcut Movement increasingly shifted their focus to a type of woodcut movement that addressed anti-Japanese activism and political themes (Nos.5-40~43). Until the end of World War II, private exchanges between the two countries through printmaking had to come to a halt.

ed.RYOJI Kumata,Hangeijyutsu No.41 Katsuhira Tokushi’s Print Collection:(Nationwide Local Toys Collection 9) Akita Local Toys Print Collection,1935

ed.RYOJI Kumata Hangeijyutsu No.45 Carved by Xiandai Chuangzuo Banhua Yanjiu-hui, Republic of China Print Collection, South China Local Toys Print Collection,1936

Chapter 6: The Birth of Postwar Printmaking – The Interplay of Central and Local Movements, and Modernism and Realism

After Japan’s defeat in August 1945, new artistic movements emerged during the occupation period. This chapter focuses on two sources: the “Ichimoku-kai” held at Onchi Koshiro’s home in Ogikubo, Tokyo, and the “Yamabiko Gakko” in Yamagata Prefecture countryside. These seemingly contrasting venues were both sources of new printmaking, stimulated by cultural influences from former enemy nations.

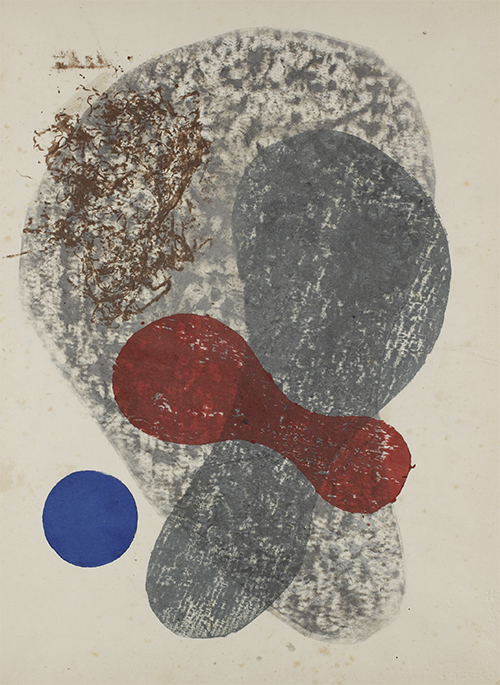

The Ichimoku-kai was a study group of printmakers who admired Onchi. It began around 1939 and continued even during the war, and after the war, it was also attended privately by American occupation forces personnel who were interested in art. When these people bought sosaku-hanga prints, the sosaku-hanga printmakers gained a financial base, and an environment for experimental expression was created. Centered around Onchi, the members created abstract works using so-called “real object blocks” or “multi block”, like leaves, strings, and paper as a print block, deepening their interest in the indirect nature of printing with blocks. The occupation forces’ appreciation of these modern abstract expressions paved the way for prints to be recognized as a modern art form, and encouraged Japanese printmakers to gain international exposure.

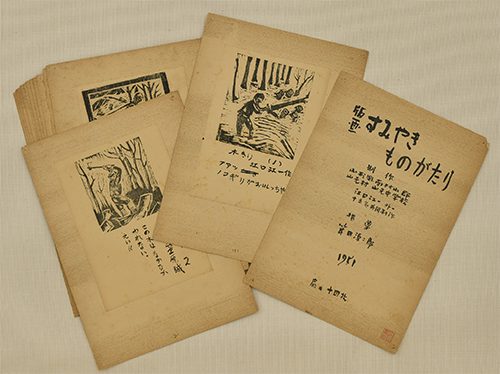

The other source was Yamamoto Junior High School, known as “Yamabiko Gakko,” in a mountain village in Yamagata Prefecture. In 1951, Chinese woodcuts were introduced to this school, known for Muchaku Seikyo’s “Seikatsu Tsuzurikata” (daily life writing) practice. The students there, moved by the “realism of labor” depicted in those woodcuts, created a print and essay anthology called the “The Story of Making Charcoal.” When this anthology was featured in magazines, teachers nationwide who had been teaching how to write began teaching how to make prints to children.

These two movements merged in the development of postwar print education. Ota Koshi, who brought them together, was a member of Ichimoku-kai and a participant in the postwar print movement influenced by Chinese woodcuts. The Japan Institute for Educational in Printmaking, centered around Ota, developed curricula for paper prints applying “real object blocks” and woodblock prints rooted in daily life, leading to the revision of the Courses of Study, and to the full-scale introduction of printmaking in elementary and junior high school education from the 1960s.

ONCHI Koshiro Lyrique No. 9 - Distant Desire,1950

Yamamoto Village Yamamoto Junior High School, Minami Muraya-ma District, Yamagata Pref.The Story of Making Charcoal,1951

Chapter 7: The Age of International Print Exhibitions –Spreading and Nurturing the " Country of Printmaking"

In the postwar period and during the Cold War, countries around the world focused their cultural policies on hosting international exhibitions. After the San Francisco Peace Treaty, Japan re-joined the international community in 1952 to focus on international cultural exchange befitting a peaceful nation, and to actively participate in international exhibitions.

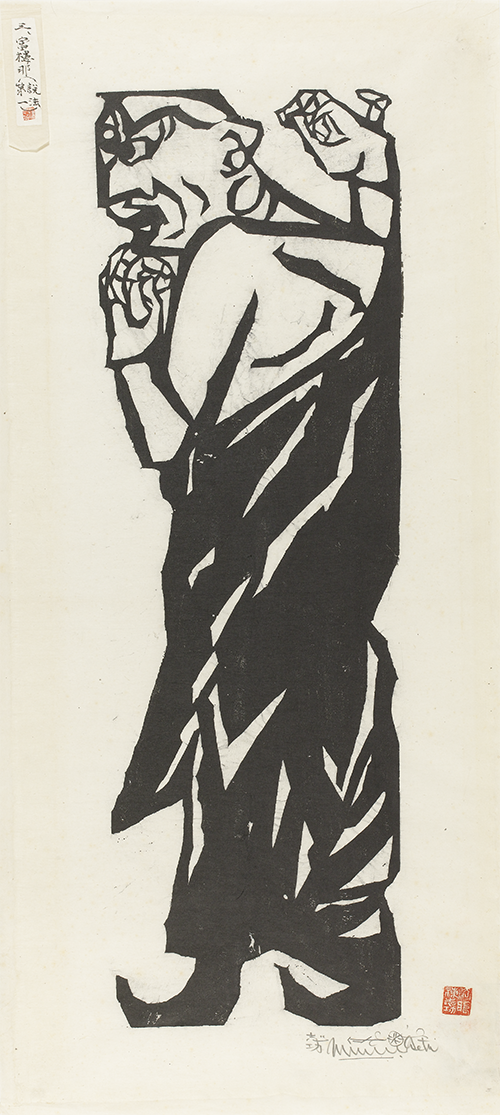

Prints on paper, which can be reproduced and transported easily, were a medium accessible for participation in international exhibitions, even from the Far East. Komai Tetsuro’s copperplate print “Momentary Illusion” (No. 7-2) won a prize at the 1951 São Paulo Biennial, marking a major breakthrough for Japanese prints other than woodblock prints. Furthermore, Munakata Shiko’s “Two Bodhisattvas and Ten Great Disciples of Sakya” (No. 7-1) winning the grand prize at the 1956 Venice Biennale demonstrated Japan's presence as a country of printmaking both domestically and internationally.

As countries, mainly in Europe, established international print exhibitions from the 1950s onward, the International Biennial Exhibition of Prints in Tokyo began in 1957, ahead of other Asian countries. The first exhibition featured contemporary prints selected by commissioners from each participating country alongside ukiyo-e displays. As the exhibition evolved, submitted works began to reflect Western contemporary art trends, with the 6th exhibition held in 1968 during Pop Art’s peak, creating buzz with the involvement of graphic designers.

During the Cold War, international print exhibitions were held both in the Eastern and Western blocs as well as in non-aligned countries. Japanese art critics served as jurors at major events like the Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts (former Yugoslavia, now Slovenia) and the International Print Biennial in Krakow (Poland), producing many Japanese prizewinners. International print exhibitions were venues where people could interact across political systems through art.

As printmaking departments were established in art universities from the 1970s, many artists who won prizes at international exhibitions went on to teach and guide new generations at universities. The development of printmaking education across institutions from elementary schools to universities throughout the postwar period laid the foundation for Japan becoming a one of the most popular countries of printmaking.

MUNAKATA Shiko,Two Boodhisattvas and Ten Disciples of Sakya Puranamaitrayaniputra,1939[exhibited until May 6th]

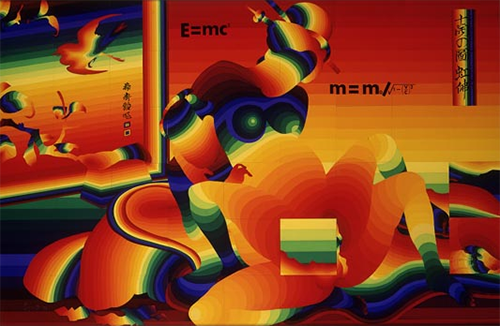

Ay-o,Rainbow Hokusai: Position A,1970